Brian kindly answered these questions for my last SF & F Buzz from Booktopia (you can sign up for the monthly Buzz edited by moi here) and just in case you missed I am pimping it.

1. To begin with why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself – where were you born? Raised? Schooled?

I grew up in New Hampshire, a small, cold state with some mountains and some rock in the northeastern part of the US. I’m sure I was raised in a house, but most of my childhood memories involve roaming the woods, building forts, fording rivers, and climbing trees. Eventually I went to college in the same state, a wonderful experience, but one in which I was forced to spend what could have been some valuable adventuring time inside studying.

2. What did you want to be when you were twelve, eighteen and thirty? And why?

When I was twelve, it seemed self-evident that there was no profession more noble or practical than that of the knight errant. Unfortunately, that sort of work fell out of vogue a while back, so I was forced to become more realisitic. I turned to poetry (both the writing and the reading), but that turned out to be even less profitable than knight errantry, not to mention the fact that it involved considerably less exercise. Finally, by thirty, I’d realized that I wanted to write books, and so I set out to do so, not realizing quite how long it takes to write an actual book.

3. What strongly held belief did you have at eighteen that you do not have now?

I thought the big things mattered more and the little things mattered less.

4. What were three works of art – book or painting or piece of music, etc – you can now say, had a great effect on you and influenced your own development as a writer?

As I kid, I devoured Ursula Le Guin’s novels, reading almost entirely for the dragons and the unnamed shadow monsters and such. Later, I realized just what a staggeringly good prose stylist she is, and just how brilliantly she’s able to bring her questing, generous, unflinching sensibility to any topic she chooses. She is, in my mind, the ultimate example of a writer who can tell a ripping good story while, at the same time, crafting sentences and paragraphs that invite reading, and re-reading, and re-reading. The same goes for William Faulkner – dazzling writing, nail-biting plot-lines – but Faulkner lacks Le Guin’s seemingly effortless mastery. I love Faulkner, but you can always hear him muttering in the background.

Then there’s Johann Sebastian Bach. Whenever I feel like I’ve accomplished something, literary or otherwise, I just listen to a little Bach. Something like the D-minor chaconne makes my stacking the wood or writing a chapter feel like pretty meager fare… but then, I get to listen to Bach, the amazement of which more than makes up for my own failings.

5. Considering the innumerable artistic avenues open to you, why did you choose to write a novel?

The scope. A novel (or a series of novels) offers more range than just about any other art form. There are no length constraints on a novel (don’t tell my editor I said that), and while each genre has its tropes and tendencies, there are no strict formal requirements. I spent many years writing poetry, an experience that felt like being hunched over a jeweler’s bench trying to set tiny gems into intricate settings. I enjoyed that work, and found it excellent training, but eventually I started to get a crick in my neck. After a while, I got tired of squinting. Writing a novel feels more like building something huge – maybe one of those neolithic burial mounds – that takes forever but that allows you to dig down into the earth as far as you want, or to look up at the position of the sun.

As far as non-writing art forms go? Well, if you heard me try to play the banjo, you’d understand why I don’t play music. And let’s not even get into the visual art thing.

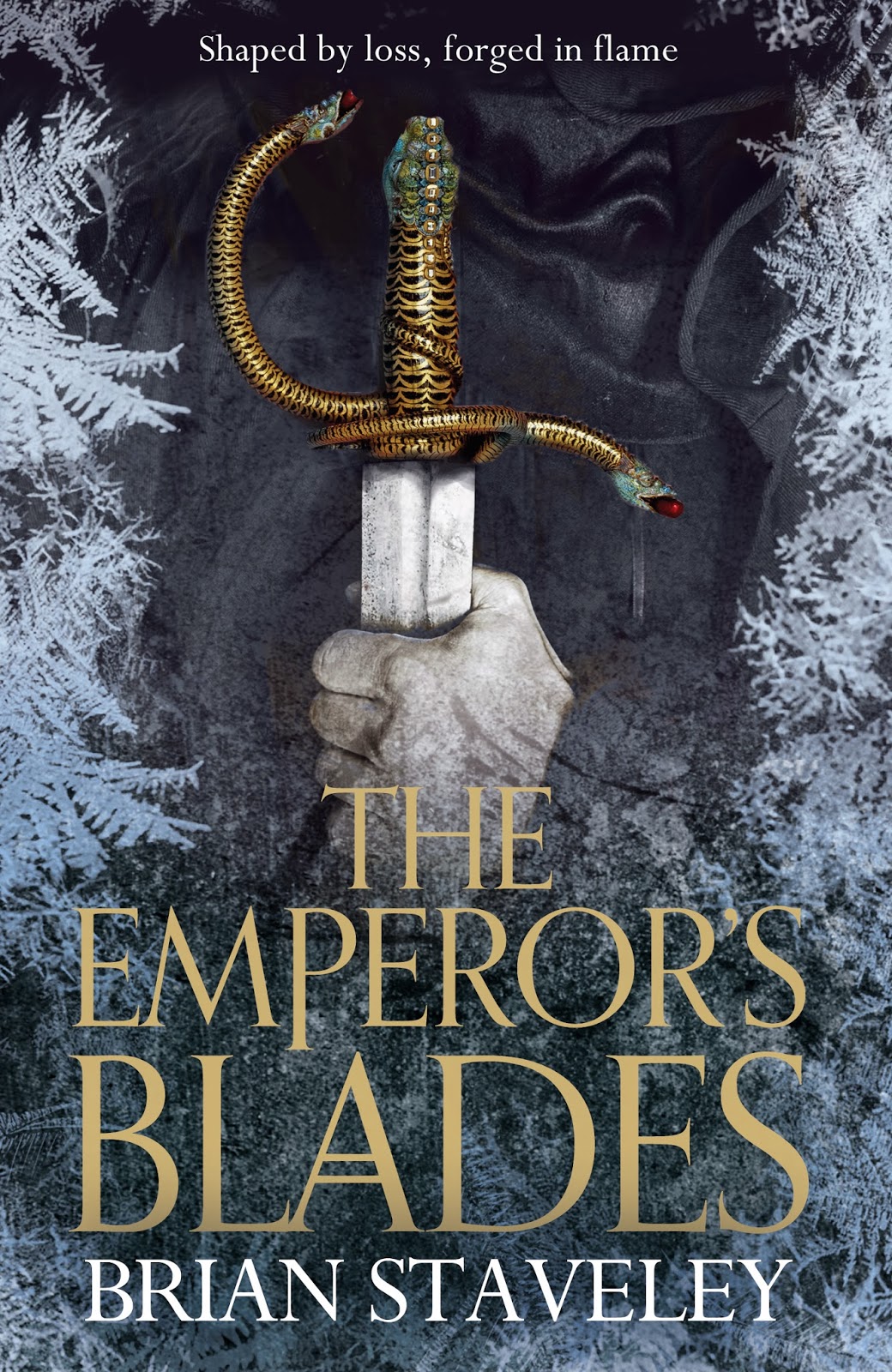

6. Please tell us about your latest novel…

The Emperor’s Blades tells the story of three adult children of a murdered emperor – two sons and a daughter; a monk, an elite warrior, and a politician – who are trying to uncover the plot that led to their father’s death. This proves a harrowing task in its own right, and is made harder by the fact that their own lives also seem to be in danger. Even worse, as the novel progresses, the goals of the unknown murderers start to look larger and more terrifying than the simple usurpation of a single empire.

7. What do you hope people take away with them after reading your work?

Whenever a new reader emails me to say she stayed up until 3AM finishing the book, and that I can go to hell because now she’s useless at work today and irritated that the next book won’t be out for nine months, I consider that a success.

8. Whom do you most admire in the realm of writing and why?

I admire anyone who sits down with a story to tell and works as hard as she can, as long as it takes, to tell it well.

9. Many artists set themselves very ambitious goals. What are yours?

I’m not sure my ambitions are so grand. If people love the books and I’m able to avoid becoming a hunchback from using the computer sixty-two hours a day, I’ll be happy. Oh, and I suppose I want my son (who is now just a year and a half old) to pick up one of my books some day and think I did a good job.

10. What advice do you give aspiring writers?

Don’t expect it to get any easier.

Brian, thank you for playing.